Meet Lorraine Glessner | Artist, Educator, Mentor

We had the good fortune of connecting with Lorraine Glessner and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi lorraine, any advice for those thinking about whether to keep going or to give up?

Live in the mindset of never giving up, no matter what. There is always another path to take, always another decision to make other than giving up. You simply have to make up your mind that giving up is not an option and when other options present themselves, you will be open to them.

The following is a personal story of not giving up even when it seemed impossible, of persevering through a very dark time, facing my fears and realizing it will all be ok in the end. The time this story took place was one of the most painful of my life, but I wouldn’t be the artist, teacher or mentor I am today without having lived through that pain and the subsequent growth that took place as a result of moving myself out of that pain. If you are stuck or need prodding like I did when the events in this story took place, reading this story might help inspire and nudge you out of your rut.

The Grass IS Greener: A Life Changing Artist Experience

In 2014 I was awarded my first month long residency at Jentel Artist Residency in Banner Wyoming. I applied for this residency in 2013 out of utter desperation. I had been grieving the sudden loss of someone very special to me and as a result, I hadn’t been in the studio or made any work for over two years. If I was no longer making art, I technically was no longer an artist and I had theoretically given up my dream of doing what I love. I was steeping in depression, guilt, life altering grief and all the rest of what comes with a downward spiral of loss. I couldn’t have made art if I wanted to at that time. When I did receive an invitation to this residency, it offered a single ray of hope and I grabbed it.

I drove from my home in Philadelphia to Wyoming-a first for me to travel that far on my own. Although I had been out west many times, I had never traveled at ground level, witnessed the marked changes in terrain, the changes in the light from blue to green to gold or watched the sunset for three hours as I drove due west. As I made my way further away from my home, I felt the mountains of guilt, grief and depression fall away from my shoulders and as each mile passed, I felt lighter and more free.

The residency is located on a thousand acre working cattle ranch with trees, foothills, desert flowers, a lovely creek, rattlesnakes, deer and porcupines. I was in love at first sight with the raw beauty of the land and the huge sky that I could see for forever. Behind the house was the tallest mountain on the property and for some reason, I got it into my head that before the end of the month I would climb that mountain. This was a ludicrous thought because for one, I’m afraid of heights and two, I had never climbed anything resembling a mountain. However, these pesky logistics didn’t matter to me. Come hell or high water, I was going to climb that mountain and I was also going to break my two year slump and make some work during this residency.

During the month, I hiked those thousand acres, exploring each foothill, memorizing the curves, drawing the contour of the land against the sky with grasses I collected and dipped in ink, hearing nothing but the wind and my own breathing as I walked and worked. This strange, brown and barren land was healing me step by step as I hiked, line by line as I drew, breath by breath as I listened to the wind. I kept an eye on my mountain nemesis behind the house, everyday assessing the height, the verticality, the rocks. It loomed and taunted me, just as the challenge to let go of my depression and get out of bed everyday seemed to loom and taunt me.

It didn’t happen for me right away but by almost 3 weeks into my month long residency I finally had a breakthrough in my work and it all started to flow. I made about four paintings, a ream of drawings and about 1000 digital drawings by the last week. I was definitely on fire, determined and inspired. The residency had done for my studio work all I had hoped for and more.

But. I. Still. Hadn’t. Climbed. That. Mountain.

Ok, so I never told anyone I was going to do it. I never made any promises to anyone, except myself, of course. It certainly wasn’t a requirement of the residency program that I climb it. Who would know if I didn’t do it? Well..I would know..and I would feel like a total failure even with all of the studio success I had achieved.

So…On the second to last day before I was to leave, it was now or never. It was a lovely day for a hike and just as I had done most days, I woke up, put on my backpack and hiking shoes. But instead of heading out to the thousand acres, I went behind the house and started up the mountain. It was much steeper than I thought and at some points, it was almost vertical with nothing but scree in most places. I had no climbing equipment and I had absolutely no idea what I was doing from a mountain climbing standpoint. I just started, one foot in front of the other… grabbed, slid, sweated and breathed my way up, paying close attention not to look down. To pull myself up the sheer verticals and to stop myself from falling when I slipped, I held on to the the tall grasses, they were my lifeline-just as they had been in the studio when I made those first drawings in ink.

At one point I did look down and immediately panicked.

I had climbed so far, there was only a short distance left, but what lie ahead of me was nothing but rock and a sheer vertical, I had no idea what to do. My heart started to pound and I couldn’t breathe, I had to sit down. As I sat there on the rock, crying, paralyzed with panic, contemplating the embarrassment of butt sliding back down in defeat…or worse, having to be rescued, I heard something breathing behind me…it was a deer! She was pretty close and seemed a bit skittish, but more confused at what I was doing all the way up there on her turf. She quietly turned around and went over the top of the mountain. I kept an eye on her path and followed it..hand over hand, step over step, gripping anything I could, even digging my fingers into the dirt to pull myself up and finally I made it to the top. I turned around to look at the ranch below me and snapped a picture so I would never forget that moment. I still remember how victorious I felt and it was then that I knew everything would be okay. I was strong and I could get through my grief and depression and move forward. I would never be the same as I was before, I would never make the work I was making before, but everything was going to be okay. I was going to be okay.

As I turned to continue down the other side of the mountain, I was relieved to see a green meadow with flowers, a clear path and an easy, gradual descent down into the valley.

Can you open up a bit about your work and career? We’re big fans and we’d love for our community to learn more about your work.

My start as a professional artist was not an easy one. Although it was not my choice, I went to design school instead of art school. The school was Philadelphia College of Textiles and Science, now Thomas Jefferson University and my major was Textile Design. Throughout my schooling and subsequent ten year career as a textile designer, I learned the fundamentals of design; composition, color, scale, repetition, etc. and acquired a detailed painting hand by countless hours of DOING. My first job out of school was as a jacquard designer for home furnishings. The company was unique in that I could take on a line of fabrics and design everything from start to finish-from the painted designs, to choosing the weaves and colors, to correcting errors in the weaving mill and on the computer. I learned an exponential amount about all aspects of design and because I had to spend hours correcting the shape of a flower on the computer if I painted outside the lines, I developed a very tight painting hand and eye for detail. The mill had been a former tie manufacturer and my design bosses, the new owners, had kept within the traditional style of florals, damasks and allover patterns, small to large scale. Designing fabrics for a large scale area like a wall or sofa presents certain problems in that the design must ‘flow’ evenly without certain elements creating a distracting line. Looking out for these kinds of design no-no’s helped me develop an excellent eye for balance and placement as well as that continuous flowing line still so prevalent in my work today.

After nostalgically writing that last paragraph, I must confess that I hated that textile designer job, I found so much of it creatively stifling and perfection seeking. Thirty years later, I am grateful for certain aspects of working as a designer and I’m certain I wouldn’t be the artist I am today without that early training. It’s fun to look at these designs and see how my textile design background influenced my early encaustic paintings as well as the work I do today

Fast forward to my mid-thirties when I finally got the chance to attend art school at the graduate level on a Fellowship in the Fibers & Materials Studies Department at Tyler School of Art in 2001. I was working with ideas related to creation and the cyclic nature of life-imprinting, staining and marking as it relates to birth through to death and decomposition. More specifically, I was interested in the physical mark and pattern of this cycle on the earth and body. I began making visual comparisons using these kinds of patterns with images I took myself or found on the internet. Some of these were uncanny in their similarities and I found this fascinating.

At the same time I was doing this research I was also looking for materials and processes that could replicate these patterns. Simply copying them or painting them didn’t work and looked contrived, I had to make these patterns via mark-making and process. I developed my own process of rust printing and staining on textiles using decomposing organic matter and the results were more amazing than I expected. Using natural processes to depict natural processes also supported my content, it was astoundingly brilliant.

I came into the graduate program as an art quilter, hand dyeing my own fabrics and sewing large beaded and painted creations that included everything but the kitchen sink. I loved quilting and wanted to expand on what a quilt could be based on the simple definition, ‘three layers of material stitched together from front to back’. I used the fabrics I had created combined with papers, image transfers, mark-making, burning and lots of machine and hand embroidery. I spent the next year sewing very large, intricate quilts (which I later stretched and called paintings) for my upcoming graduate thesis show.

One of the experiments I had done was to dip my stained and rust printed fabrics into encaustic medium and really liked the way it added depth and enhanced the marks on the fabric. Since I had been stretching the sewn pieces into paintings, why not do the same here. I mounted the fabrics using wax, only using minimal color and letting the stains and marks speak for themselves. I made ten of these paintings and hung them in the small room adjacent to the main gallery, which housed my large sewn pieces. The opening was in the gallery district in Philadelphia on First Friday so we had a packed house and there were so many people in that tiny room ogling my encaustic paintings, one could barely move. People were interested in the sewn paintings but it was sparse interest and they sparked no real discussion, everyone wanted to know about the luscious paintings in the tiny room. The icing on the cake was that I also sold one of the encaustic pieces to someone I didn’t know, wasn’t related to and was a museum curator. This was the first thing I had ever made in my 30-something years that had sold, so I saw it as some kind of sign that encaustic is what I should be doing.

I followed all the signs and immediately abandoned the sewn paintings to continue exploring the fantastic medium of encaustic which I have loved and made my own at the same time the medium itself was becoming it’s own. Over the years, I added more color, collage, image, hair, mark-making and investigated various ideas, although my core ideas have remained rooted in the earth. The rest, as they say, is history and encaustic and I continue to live happily ever after.

While writing my article chronicling my early journey with encaustic, I realized that I learned many valuable lessons through it all. Three lessons stood out as being most important while at the same time being those lessons that I’m constantly re-learning as I go.

When I’m teaching, I always begin each day with a quote that works to set the tone for that day and almost always it’s a quote from Art & Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland. If you haven’t read it, go get it NOW, read it once and then turn around and read it again. I quote from it often because I read it often, roughly once a year since it was first introduced to me in graduate school. My copy is highlighted almost all the way through because each time I read it I find another valuable snippet that seems to speak directly to me and the struggles I may be going through at the time. All of the quotes from this book were used to write this article unless otherwise noted.

1. Experiment often with current and new materials, make lots of samples, document and save them.

“What you need to know about the next piece is contained in the last piece. the place to learn about your materials is the last use of your materials. The place to learn about your execution is in your execution. The best information about what you love is in your last contact with what you love. Put simply, your work is your guide.”

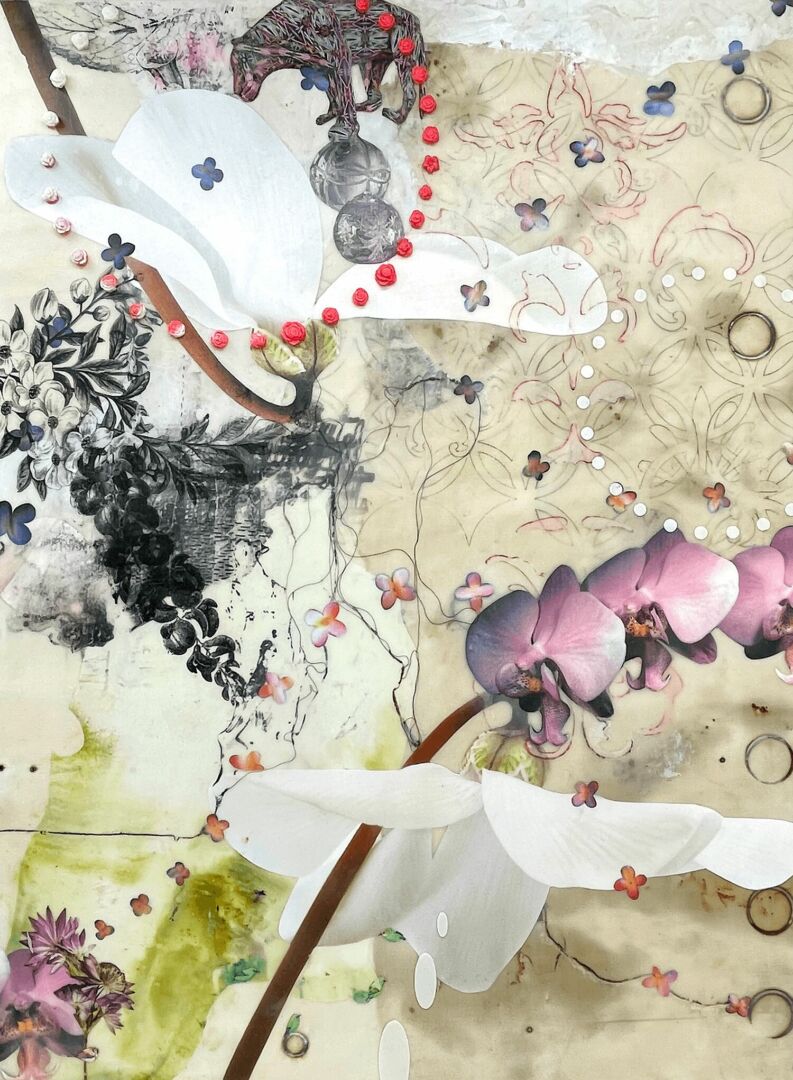

I can’t recall where I first heard the 40/60 principle or even if I’m getting the percentages right, but it’s something we all must strive to do. The principle works something like this…60% of your studio work should be spent making work you are known for and/or work you are ‘comfortable’ making using materials, processes and ideas you know well. The remaining 40% should be spent experimenting with new materials, processes and ideas which will generate new work. If you keep doing this, sooner or later the ‘new’ work begins to seep into the current body of work and eventually it becomes your current body of work. If you apply this principle, your work and you as an artist, will continuously evolve and grow. This sounds great, but many artists may find it difficult to work experimentation into their busy and sometimes, very limited, studio time. What I’ve done to keep experimentation alive in my studio is average my daily hours and experiment for a percentage of that time-usually about 30 minutes to an hour for every 6-8 hours. I call this work my warm-up drawing time and sometimes will work on the same drawing all week, applying new layers each day (see the featured image above). I have so much fun just playing around with materials in the studio that I’ve forgotten about. Many times, this experimentation has generated new bodies of work that I would have never conceived of without first experimenting.

“Vision is always ahead of execution, knowledge of materials is your contact with reality, and uncertainty is a virtue.”

I don’t mention this in my last article, but my first year of graduate school was very difficult for many reasons. My first review was at the end of my first semester and it was coming up fast, so fast that I was in fear of not having anything to show. One of my committee members suggested just having a wall of samples for my review. I had a few samples, but not nearly enough so I spent 3 straight weeks barely coming out of my studio to make hundreds of samples. Only having limited time as well as keeping in mind that these were just samples prevented me from being too precious and worrying about making a ‘finished’ work. Those three weeks were perhaps the most painful but most prolific of my total two-year experience-more importantly I learned so much about what my materials could do and what I, as an artist, could do. I saved almost all of those samples and I still use most of them as teaching tools today, both in workshops and in my own studio.

2. You don’t always have to know what you’re doing. This lesson could be read two-fold: a) You don’t always have to know HOW to do what you’re doing and b) You don’t always have to know what you’re going to make-what it’s going to look like.

“People who need certainty in their lives are less likely to make art that is risky, subversive, complicated, iffy, suggestive or spontaneous. What’s really needed is nothing more than a broad sense of what you are looking for, some strategy for how to find it and an overriding willingness to embrace mistakes and surprises along the way. Simply put, making art is chancy-it doesn’t mix well with predictability. Uncertainty is the essential, inevitable and all pervasive companion to your desire to make art. And tolerance for uncertainty is the prerequisite to succeeding.”

This is likely my favorite quote of all time and I read it in every workshop. It is absolutely essential to keep experimentation, the idea of imperfect perfection and the element of chance in the work at all times. This doesn’t mean I’m encouraging you to make sloppy or ill-conceived work, rather, allow for a symbiosis to occur between you and your materials. Allow your materials to do what they do and you to push them gently in a certain direction. Full control and technical perfection is the death-knell for any work of art. It’s in the imperfections that true art is made and is the predominant concept behind the Japanese principle of Wabi-Sabi–an awesome subject for any artist to know, but far too complicated to explain here. The best book I have read on the subject is Wabi-Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence by Andrew Juniper and Wabi-Sabi for Artist, Designers, Poets and Philosophers by Leonard Koren is also good.

When I first started working in encaustic, there were no books to refer to, no workshops and barely any information online, so I was basically on my own. I used tools that I already had in the studio, combined encaustic with other materials, basically developed my own processes and ways of doing things with this medium. The result was that I developed a truly original body of encaustic work. I absolutely believe that if I had taken an encaustic workshop, I wouldn’t have developed this work or perhaps it would have come much later. On the other hand, taking an encaustic workshop would have saved me two years of improperly ventilating wax fumes as well as understanding the importance of fusing and the reasons why Damar resin is added to the beeswax. While it’s okay not to know too much, ALWAYS work safely and technically accurate with your materials. Once you know those things, have fun and let things happen!

Last, a great story illustrating the woe in striving for perfection comes from Art & Fear….

“The ceramics teacher announced on opening day that he was dividing the class into two groups. All those on the left side of the studio would be graded solely on the quantity of work they produced, all those on the right, solely on the quality. His procedure was simple: on the final day of class he would bring in his bathroom scale and weigh the work of the quantity group: fifty pounds of pots would get an ‘A’, 40, a ‘B’, etc. those being graded on quality needed to produce only one pot-albeit a perfect pot to get an A. Well, came grading time and curious fact emerged: the work of highest quality were all produced by the group being graded for quantity. It seems that while the quantity group was busily churning out piles of work and learning from their mistakes, the quality group had sat theorizing about perfection, and in the end, had little more to show for their efforts than grandiose theories and a pile of dead clay.”

Remember this story every time you strive for perfection and find yourself overworking a piece into oblivion.

3. Don’t start working on a white background.

“Inspiration is for amateurs; the rest of us just show up and get to work. If you wait around for the clouds to part and a bolt of lightning to strike you in the brain, you are not going to make an awful lot of work. All the best ideas come out of the process; they come out of the work itself. Things occur to you. If you’re sitting around trying to dream up a great art idea, you can sit there a long time before anything happens. But if you just get to work, something will occur to you and something else will occur to you and something else that you reject will push you in another direction. Inspiration is absolutely unnecessary and somehow deceptive. You feel like you need this great idea before you can get down to work, and I find that’s almost never the case.” –Chuck Close

The fear of the white canvas isn’t new, we’ve all experienced it in one way or another and have developed our own methods of fighting it. I always tell my students that art begins in the head with an idea, flows through the heart, which makes it personal and out through the hand, which makes the actual work. Too much emphasis in any one of those places creates an imbalance in the process. Whenever I have developed a finished work in my head and then tried to make it, I almost always fail due to the frustration that it isn’t coming out ‘right’. The same thing happens when I try to plan too much before beginning a piece, I get mired in the planning stage and never actually DO anything. The best method for me and one that I suggest to students is to develop a step-by-step process that will generate a mark, then follow or respond to that mark. The less control you have over that initial mark, the better.

Covering a board with a stained or rust printed fabric and then responding to those marks was the process I developed in grad school. This process enabled me to create subsequent marks to generate paintings I never would have had I started with a white board. It was also important that I didn’t have total control over the initial process itself-in a sense the process controlled me and that was just fine.

If you had a friend visiting you, what are some of the local spots you’d want to take them around to?

I would likely take them on a museum trip to all of my favorites in my city of Philadelphia. If you visit the Philly area and want to see a lot of art, you can use this as a guide for the amount of time you’ll need at each museum and gallery.

Below is a list of all the art museums in the Philadelphia area that I personally enjoy. Mind you, this is not counting all the excellent commercial galleries, university galleries, studio buildings and art spaces in this awesome art city. For the sake of time and space, I’m limiting this answer specifically to art museums in Philadelphia proper.

The first thing you’ll want to do is go online and research if the museum is presenting any special exhibitions and/or what is on display during the time you’ll be there. Prioritize what you want to see first to last.

Next, figure your schedule to be 2–3 hours of art viewing and then take a break for an hour or so. Go out to lunch, go outside and take a walk, go for a bike ride, do whatever, just stop looking at art for a little while. Most of the museums will allow you to leave and come back without having to pay again. Just make sure you keep your pin and receipt so you can show it when you return.

If you follow this plan, you can see art in the morning, break, afternoon, break and even go after dinner to the museums which have night hours.

1. PMA Philadelphia Museum of Art There is so much here, it will take a day at least to see the whole. Give yourself time and space and first see the galleries most important to you. The gardens and Water Works just outside offers a good place to clear your mind while taking a break. The museum also has night hours once a week so you can portion out your day.

2. The Barnes You’ll definitely need to schedule a lot of time here or you’ll overload quickly! I would say this will take a whole day and possibly the evening- this museum also has night hours once a week.

3. The Franklin Institute I wouldn’t call this an art museum, per se, but it can be very inspiring for the creative mind. You could probably do this in a three hour time slot.

4. African American Museum in Philadelphia Always something interesting and inspiring on display here. It’s smaller than the Barnes, PMA and Franklin Institute, so you would only need a morning or afternoon here.

5. National Museum of American Jewish History Another interesting and inspiring museum with tons of objects and learning to be had. Depending on interest, you could do this in a morning or afternoon.

6. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts One of my personal favorites, I always see something good here no matter when I happen to visit. Again, not as large as the first museum listings and can be seen in a morning or afternoon.

7. The Mütter Museum I have always loved this place and would often have lunch in the gardens here when I worked in the city. There is a ton to see here and the special exhibitions are always interesting. You might need a whole day to see all that’s here.

8. The Fabric Workshop and Museum Another of my personal favorites, it’s pretty smallish and can be seen in a few hours.

9. Woodmere Art Museum This museum is a bit outside of Center City, but it’s definitely worth the trip. It’s a small museum, but it’s always got something interesting to see. It’s also got a great outdoor sculpture garden-pack a lunch and make it a day.

10. Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens A totally joyful place, it’s impossible not to feel good here and it’s definitely a must see if you love art, your eyes will be happy. This will take only a couple of hours as it is a small space.

11. Eastern State Penitentiary Another definite must-see and one of my personal favorites. This will satisfy the art/history lover in you as well as the lover of creepy. I love all of those things and can’t stay away from this place for the photo ops, unique history and rotating art installations in the cells and grounds. You could probably do this in a 3 hour segment and there are also lots of great places to eat in the surrounding area.

12. Rodin Museum A good one to schedule on the days when you’re at the Barnes and PMA, they are all very close together. This is the smallest of the three and could be seen in a morning or afternoon.

Who else deserves some credit and recognition?

To my husband, Todd, who has always supported me in my work, even when it has taken me on long road trips away from home and sequestered me in my studio for long periods of time. Being the spouse of a teaching artist is not an easy road and he deserves a big shoutout dedication. xo

Website: https://www.lorraineglessner.net/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lorraineglessner1/

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lorraine-glessner-4a39aa6/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lorraine.glessner.3

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCfPQcv0XgzamVVK9dbRo8vA?view_as=subscriber

Image Credits

Lorraine Glessner