Meet Zico Albaiquni | Artist & PhD Candidate at University of Melbourne

We had the good fortune of connecting with Zico Albaiquni and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Zico, can you tell us more about your background and the role it’s played in shaping who you are today?

I’m from Bandung, Indonesia, a city surrounded by mountains and rich in both traditional culture and colonial history. I grew up in a family deeply connected to the arts—my father is an artist and activist, and my mother a teacher. Their worlds shaped me early on: my father introduced me to the power of images and performance as resistance, while my mother grounded me in care, discipline, and spirituality.

Growing up in post-Reformasi Indonesia, I witnessed a nation constantly negotiating its identity—between inherited colonial frameworks and local traditions. This tension influenced the way I saw painting—not just as a Western invention, but as something that could be reclaimed, localized, and reimagined. I began questioning why certain aesthetics were seen as ‘low’ or ‘vulgar’ and realized those were often rooted in class and colonial prejudice.

Today, that upbringing shapes my practice as both an artist and researcher. I’m interested in how painting, especially in Indonesia, can become a site for decolonial thinking—a way to revisit and disrupt dominant narratives, and to bring forward the voices and aesthetics that were historically marginalized

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

I’m from Bandung, Indonesia—a city surrounded by volcanoes, colonial ghosts, and living traditions. I was raised in a household where art, language, education, and spirituality were deeply intertwined. My father, Tisna Sanjaya is an artist and activist, always told me, “seni punya daya”—art has power—and reminded me, “katakanlah meskipun pahit—dan berdoalah” (“speak the truth, even if it’s bitter—and pray”). From him, I learned that art is a space for resistance, honesty, and healing.

My mother, Molly Agustina, who is a Bahasa Indonesia teacher, instilled in me a love for language and structure. She believed that words shape the way we think, and that education—especially through our own language—can guide us toward a more compassionate, conscious life. Her teachings helped me understand the weight of names, of phrasing, of silences, and how language can carry memory and power.

Growing up in the aftermath of Reformasi, I witnessed a country still haunted by its past and struggling to imagine its future. Now, as we watch that democratic promise unravel—under the shadow of unchecked power and oligarchy—I find urgency in what I do. Painting has become a space where I gather the voices that have been ignored, images that were never seen, and documents that were never allowed to surface—like a lost receipt, a censored memory, or a song that never made it to the archive.

That’s why I use the term lukisan instead of painting. Because for me, lukisan isn’t only something to be displayed—it is something in play. It performs, it remembers, it questions. It’s a layered space where the political, personal, spiritual, and historical meet. Through lukisan, I continue the legacy my parents handed down to me—where truth, language, imagination, and care are inseparable.

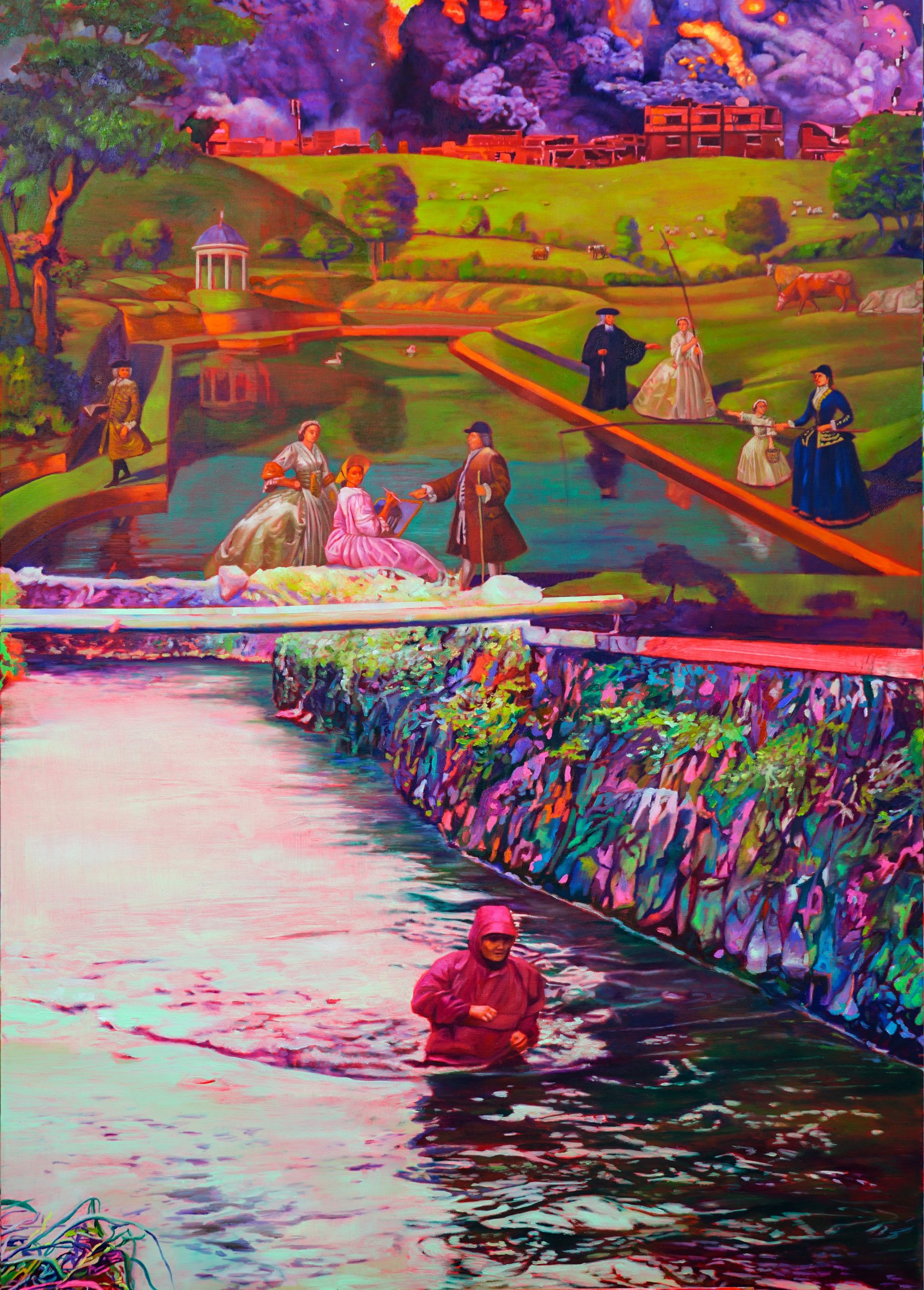

My lukisan are large, layered, and saturated in color—often colors dismissed as kampungan, or vulgar. I use these deliberately, to reclaim and celebrate the aesthetics of the people. My work responds to the legacy of colonial painting in Indonesia, especially the Mooi Indie tradition that romanticized the landscape and erased the struggles of its people. My goal is not to recreate beauty—but to disrupt it, to question who has the right to represent, and how.

What sets my work apart is how I use painting as a decolonial tool. I collage fragments of colonial archives, mix them with local mythologies, theatrical staging, and non-linear time. I often refer to my practice as lukisan rather than “painting” because I want to return to an Indonesian way of seeing and making—one rooted in ritual, land, and everyday wisdom.

One of my early breakthrough works, Doa Ibu Sepanjang Zaman (2017), began as a journey through sacred sites in Java, where I immersed myself in Sundanese-Islamic rites drawn from the Karesian Sikhsa Kandha (1518). Through this process, I explored the enduring myth of Ratu Laut Selatan and questioned how spiritual, cultural, and ecological landscapes are transformed—both through time and through art. This interest in how places carry layered histories continued in Ruwatan Tanah Air Beta, Reciting Rites in Its Sites (2019), commissioned by Framer Framed and now part of the Wereldmuseum collection in Rotterdam. The work reflects on the colonial history of the Bogor Botanical Gardens—established in 1817 as an experimental site for cultivating crops for exploitation across the archipelago. My painting traces its transformation from sacred ground and site of Javanese cosmology, to a tool of imperial science, to its contemporary role as a guardian of biodiversity. In doing so, it interrogates the colonial legacies still embedded within institutional spaces like the museum, asking how we might reimagine these entangled histories through painting and ritual.

This engagement with layered landscapes and colonial legacies mirrors the trajectory of my own path. It has never been linear. After graduating from art school, it took nearly a decade before I found gallery representation—and not in Indonesia, but abroad. Still, that long journey shaped me. I kept painting, supported by the energy and solidarity of the Gerilya Artist Collective in Bandung, which I co-founded with friends. Together, we carved out a space for experimentation, conversation, and mutual care—holding each other up when the art world felt distant or inaccessible. That spirit of collectivity continues to guide me.

Over time, I found a gallery Ames Yavuz Gallery that became more than just a professional partner—Can Yavuz, Caryn Quek and Nicole Hauser they welcomed me as part of a family. We work together, growing the practice with trust, care, and shared vision.

Alongside this, my wife Kartika Larasati and I raised our children while keeping our creative lives active, constantly navigating between care and creation, between persistence and imagination. If this process has taught me anything, it’s the importance of clarity—of knowing why you make, and for whom. My works aren’t simply images; they’re traces of relationships, cultural memory, and a refusal to be simplified or erased.

Now based in Melbourne, I live with my family while pursuing a PhD, working between two worlds—Indonesia and Australia, painting and writing, memory and possibility. I still take on part-time work, but our life here is full: our children are growing, and my partner continues to be a source of strength—grounded yet visionary, always pushing me to grow bolder in my voice and purpose.

This story isn’t just about struggle. It’s about building something that lasts—through color, through care, and through a deep commitment to where we come from, and where we’re going.

Let’s say your best friend was visiting the area and you wanted to show them the best time ever. Where would you take them? Give us a little itinerary – say it was a week long trip, where would you eat, drink, visit, hang out, etc.

If my best friend were visiting Melbourne, I’d want them to stay at my home. We’d start our mornings by making breakfast together—something simple but warm—then prepare lunch boxes that we could take with us to enjoy a picnic at the Royal Botanic Gardens.

In the afternoon, we’d take a walk by the beach near my house, maybe all the way to Point Ormond, watching the sunset and letting the sea breeze slow us down.

For dinner, we’d head to the South Melbourne Market to pick out some fresh and delicious ingredients. There’s a wide variety of beautiful produce and specialty food there. Then we’d return home and cook together—turning dinner into both a meal and a shared memory.

One of the things I’d definitely want to share with them is my and my wife’s favorite croissant: the Pandan Croissant—a flavor that reminds us of the traditional Indonesian cakes we grew up with. We’d pair that with coffee from Padre, one of the best around.

If they stayed for a whole week, I’d also invite them to join me in the rhythm of our everyday life—like walking my kids to school in the morning, which is something I truly cherish.

During the day, we’d visit galleries near my home like the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) and ACCA Melbourne, which always have exciting and thought-provoking exhibitions.

I’d also take them to my studio at The Stables at VCA, where I’d introduce them to my fellow artists—many of whom are also studying here and come from various cultural backgrounds. It’s a space full of creative energy and generous exchange.

And on Sunday, I’d bring them to Camberwell Sunday Market—a lovely, bustling place where we could walk around, chat with local vendors, and maybe pick up some interesting secondhand items or vintage treasures. It has such a warm atmosphere—it’s less about buying, more about being present.

Finally, I would make sure we visit A1 Bakery, one of my all-time favorites—and a beloved spot for my whole family. It’s simple, delicious, and feels like home.

Who else deserves some credit and recognition?

My Parent- Tisna Sanjaya & Molly Agustina

My Wife – Kartika Larasati

My Kids – Aksara Sada Albaiquni & Raga Sabdagaluh Albaiquni

My Parent in law – Dani Gunadi, Mita Karmeini

My Sisters and Brothers – Praditya Salim, Tasya Tiara, Etza Meisyara, Nadya Jiwa Saraswati, Rizal Nugraha, Adam Ghazali, Daffa Ananta Sanjaya

My Late Grandfater – R. Pardi Sukantawijaya

My late Grandma – Amih Komasih

Special shoutot to my auntie : Amy Meilani, and to all my uncles and aunties (15 from my father side, and 4 from my mother side)

My godfather – Carl Christoph Schulz

My godmother – Melanie Setiawan

My Best friends : Wibi Triadi, Aliansyah Caniago, Anggawedhaswara, Davit M. Thomas, Rega Rahman, Patriot Mukmin, Doni Dwihandono Ahmad, Tara Astari Kasenda, Ady Nugeraha, Febrian Adi Putra, Rinaldo Hartanto, Irfan Hendrian, Sigit Ramadhan, Radhinal Indra, Bob Hendrian, Tandia Permadi, Bandu Darmawan, Asep Topan, Yoga Mogo, Caitlin M. Hughes, Dimas Kaisar, Wenda Zidah, Sekar Sari, Reza Dien, Hendra Himawan, Gadis Prameswari, Alrezky Cezaria, Tazul, Bayurengga, Nugi Utomo, Teguh Cile

Gerilya Artist Collective

Sanento Yuliman and his book “Dua Seni Rupa”

My junior high school History teacher – Pak Budi

Ames Yavuz Gallery team – Can Yavuz, Caryn Quek, Nicole Hauser

S. Sudjojono

Raden Saleh

AD Pirous

Rizky Ahmad Zaelani

Bambang Ernawan

Sigit Pius

Bambang Toko

Raafat Ishak

Lisa Radford

Wulan Dirgantoro

Danny Butt

Tarun Nagesh

Aaron Seeto

Sadiah Boonstra

Greg Dvorak

R.E. Hartanto

Radi Arwinda

Erik Pauhrizi

Erka Ernawan Pauhrizi

Syagini Ratnawulan

Arin Dwihartanto

Tromarama

Mella Jaarsma

Reza Afisina

Irwan Ahmett

Melati Suryodarmo

Octora

Muhammad Akbar Babay

FX Harsono

Sativa Sutan Aswar

Wawan Husin

Om Gamal

Chloe Ho

Resika Tikoalu

Santy Saptari

Amalia Wirjono

Martin Suppan

Brett Hardy

Scott Bradford

Leo Silitonga

Konfir Kabo

Stephen Saul

and many more who I think it will make the list longer than this

Website: https://amesyavuz.com/artists/zico-albaiquni/

Instagram: zicoalbaiquni

Facebook: Zico Albaiquni

Image Credits

Ames Yavuz Gallery

Dimas Kaisar

Eva Broekema

Siam Candra Artista